“http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QER_yqTcmjM

Worf: There is the theory of the Moebius. Where time becomes a loop.

LaForge: When we reach that point, whatever happened will happen again.

(Lines from Star Trek the Next Generation, spoken by the show’s two Black actors. )

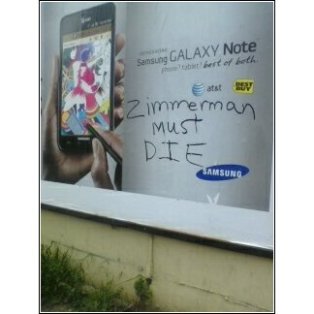

We are stuck in a Moebius. The eerie deja vu of Trayvon and The Help calling forth Rodney King and Hattie McDaniels. In Ward 8 here in D.C., Marion Barry calls Asian owned businesses dirty and I feel the heat of the L.A. riots. History is repeating itself and has been since post Civil Rights America began taking shape.

In “By the Color of Our Skin: The Illusion of Integration and the Reality of Race” by Leonard Steinhorn and Barbara Diggs-Brown, the authors analyze the post Civil Rights era to assess the effort to integrate America. The authors argue that, since the civil rights movement, Black and White integration is more common in public spaces such as workplaces, schools, and shops. They agree that this has an overall positive impact on the status of Blacks in America.

However, in private spaces, segregation is the norm. People tend to associate with members of their own race. In many cases this is because Whites fear Blacks and Blacks mistrust Whites because Whites fear Blacks. Meanwhile, in TV and movies Blacks and Whites associate with each other far more than they do in the real world, giving our couch-potato society the impression that integration has been achieved. Where time becomes a loop. Steinhorn and Diggs-Brown go on. They argue that Whites forget that the long history of White Supremacy and the legacy of Black enslavement taint many interactions that Whites deem “harmless”. Misunderstandings abound. Distance increases. I argue that this is true for all non-Black people. Black people are isolated by anti-Black racism in America.

Politicians from both parties, including Barack Obama, wax poetic about King’s dream of a colorblind society. They carefully ignore King’s belief that America would require a policy of reverse discrimination against White’s in order to correct for hundreds of years of slavery and oppression. Meanwhile, affirmative action opponents use King’s words to make sure this never happens. A colorblind society cannot, in the end, acknowledge the traumatic impact of slavery on Black people in America. But the song goes on. Where time becomes a loop.

Anti-black racism in America is real, occurring now, and unique amongst oppressions experienced by people of color in America. Tamara K. Nopper has a great piece on this in her blog :http://tamaranopper.com/2012/04/20/george-zimmerman%E2%80%99s-minority-defense-and-the-1992-los-angeles-riots/

As an Asian immigrant in America, I do not experience anti-black racism. Nor do I know what it is like to be Black in America. I do not share a history of slavery, and systematic degradation of my entire group. My people have not been called animals or less than human. My people have not been marginalized from work. My people have not been imprisoned en masse. My people are not seen as lazy, or chronically poor. I do not carry the weight of these stereotypes on my shoulders. And when I behave in ways that counter these particular stereotypes I am not accused of acting White.

I have worked in coalition with Black women as part of women of color organizing. I have been enriched by these interactions and I hope I have been an ally to them. But the truth is, our groups’ causes are not the same. Unless I acknowledge this, I cannot be sure that I am being an ally to Black women. Unless I truly get this, the things I do in the name of racial justice for all may in fact be singing the same old colorblind song. Where time becomes a loop.

How can America break free from this colorblind loop? How can America break free from this colorblind loop? How can America break free from this colorblind loop. How can America break free from this colorblind loop?

By seeing the colors and knowing their stories. Steinhorn and Diggs-Brown offer a few ideas on how to do this as it applies to anti-Black racism in America:

1. Stop trying to achieve the integration gold star. Whites and Blacks don’t have to do everything together in order to peacefully coexist. In India we have 20 something states, each with its own language, culture, film industry, and food. People still relate to each other enough that they can have a national government that functions.

2. Do something to atone for slavery. The playing field is in no way level after 400 years of systematic subjugation. Acknowledge it. Make it a national priority. Tell people who don’t like it to suck it up and move somewhere else.

3. Put real race talk on TV everywhere. In shows. In public service announcements. We need some MadMen style campaigns to counter anti-Black bias in America. End tokenism and increase the number of shows that reflect the real internal lives of different groups of people.

4. This one is based on my own thinking and is backed up by Tamara Nopper’s piece. Stop lumping people of color together. And that means non-Black people of color need to get on board with acknowledging anti-Black racism as singular. We need to recognize that justice for Black people is at the core of achieveing justice for all people in America. When Black people talk about how something is racist like “The Help” (see another Tamara Nopper piece http://tamaranopper.com/2012/02/28/be-the-help-campaign-black-disappearance-among-the-multiracial-left/) we need to listen and ground our own actions on analyses generated by Black folks.

That doesn’t mean the struggles of non-Black people of color are not important. Native people in America also experienced a singular oppression based on colonization and genocide. The experience of immigrant people of color is another experience entirely. Chicanos who were crossed by the border fight another battle altogether. Muslims in America today are demonized in ways I can only sense from being mistaken for Muslim. We must see these differences clearly in order to strategize and support each other. We don’t have to stay on the merry go around trying to make our horse go up while others go down. If we do, “when we reach that point, whatever happened will happen again.” Where time becomes a loop. Where time becomes a loop.

Steinhorn, L. & Diggs-Brown, B. (2000). By the color of our skin: The illusion of integration and the reality of race. Plume. NY.